Women are Twice as Likely to Die of Heart Attack Compared to Men

The belief that women are 'tiny men' led to using male symptoms to diagnose female cardiac events... poorly.

Co-authored by Taisiya Reed and Julie Markhus.

This stat blew our hair back when we first heard it. How could it be that women would be twice as vulnerable to such a well-known (and well-represented in the media) acute event? Once again, the research (or lack thereof) shows how badly needed change is.

Background:

Women are twice as likely to die once presenting with a heart attack than men. (European Society of Cardiology, 2023)

Women are twice as likely to die of coronary heart disease than breast cancer in the UK. (British Heart Foundation), still not seen as a female ‘health’ problem.

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide for both men and women. (WHO)

Men are more often screened and advised for heart attacks than women, as it is commonly thought of as a male issue. (American Heart Association, 2020)

Biological sex differences:

Heart disease affects men and women differently

Female hearts have different sizes and shapes compared to males. Women also have smaller blood vessels. This causes men and women to develop heart disease differently. (O’Donoghue)

Heart disease often develops due to cholesterol buildup in the blood vessels. As women’s blood vessels are smaller, females tend to develop plaque in the smaller peripheral blood vessels while men more often develop plaque in large central arteries. (O’Donoghue)

One study found that people who had endometriosis have a 3 times higher chance of developing heart attacks compared to people who do not have endometriosis. (Wise et al. 2016) Even though the underlying mechanisms are not known, female hormones seem to play an important role in cardiovascular health.

Women tend to develop heart disease later in life. (Harvard Health)

Women often experience different symptoms of heart attacks than men, such as nausea, fatigue, and loss of breath, which can be seen as more diffuse. (Harvard Health)

Women typically do not develop heart disease until after menopause, as high estrogen levels lower LDL cholesterol levels and improve blood vessel health. As these hormones decrease during menopause, women lose this natural protection from plaque build-up in arteries, which often causes heart disease. (El Khoudary et al. 2020) This is a natural difference between the sexes.

Women have historically been excluded from studies on heart disease, often because of age. Women tend to present with heart disease later in life due to hormonal changes. (Gurwitz, Col and Avorn, 1992) They are also diagnosed on average 7-10 years later. What are the consequences of excluding them from clinical trials?

The gender gap in Diagnosis:

“Our findings suggest a gender gap in the first evaluation of chest pain, with the likelihood of heart attack being underestimated in women,” said study author Dr. Gemma Martinez-Nadal of the Hospital Clinic of Barcelona, Spain. “The low suspicion of heart attack occurs in both women themselves and in physicians, leading to higher risks of late diagnosis and misdiagnosis.” (Antipolis. 2021)

A common blood test to diagnose heart attacks is troponin. However, women have been found to release less troponin than men when they have a heart attack. Yet, there is no difference in the threshold between men and women when analysing the test. Most women with heart attacks do not release enough troponin to cause a positive test. (O’Donoghue)

Another gold standard test for diagnosing heart attacks are cardiac cathetarisation which looks for blockages in the major arteries. However, due to women’s anatomy, women tend to have blockages in the small arteries. Consequently many women who have heart attacks will have a false-negative test. (O’Donoghue)

Due to different symptoms between men and women in heart disease, women are more often misdiagnosed compared to men. (Collins et al 2011)

Both clinicians and patients are less likely to think that a woman with chest pain is experiencing a heart attack, compared to a man with chest pain. This perception often cause misdiagnosis or delayed diagnosis. (Antipolis, 2021)

Women are less likely to receive invasive diagnostic procedures such as angiography and revascularisation when they are hospitalised for coronary heart disease. (Ayanian and Epstein, 1991)

Women are 59% more likely to be misdiagnosed when they present with the most severe form of heart attack (complete coronary artery blockage), than men. (Nadarahaj et al. 2024)

The gender gap on Treatment:

Why women and men should be treated differently for heart disease.

Women are likely to receive aggressive treatment compared to men, such as beta-blockers of angioplasty. (Lezen et al. 2007)

Medication such as aspirin and statins have been shown to work differently in women as compared to men. (Xhyheri & Bugiardini, 2010)

Women are less likely to receive pacemakers than men. Women are less likely to receive advanced devices such as cardiac resynchronisation therapy (CRT). Overall, there are significantly lower referral rates among female patients. (De Silva et al. 2022)

The standard pacemaker was made to fit male hearts size and shape, which is different from female hearts, making the first pacemakers difficult to fit in female hearts. There are also biological sex differences causing differences in heart rate and electrical system in the heart, where the pacemaker was only designed and tested on male features. The underrepresentation of women in these studies caused these critical devices to be designed based solely on male anatomy. Many researches suggest that a female pacemaker should be fitted differently to better fit their anatomy. However, clinical trails are needed to confirm this. (De Silva et al. 2022)

Women are more likely to respond better to B-blockers and have worse reactions to pacemakers compared to men. (Barsheshet et al. 2012)

Women are more likely to have an adverse drug reaction to treatment for heart disease due to different body composition, hormone levels and metabolism than men. (Tamargo et al. 2017)

BHF-funded study finds that women gets half the number of treatments as men. (Wilkinson et al. 2019)

Should women receive different treatment for cardiovascular disease? Many people think so? (Regitz-Zagrosek et al. 2016)

The gender gap on Prognosis:

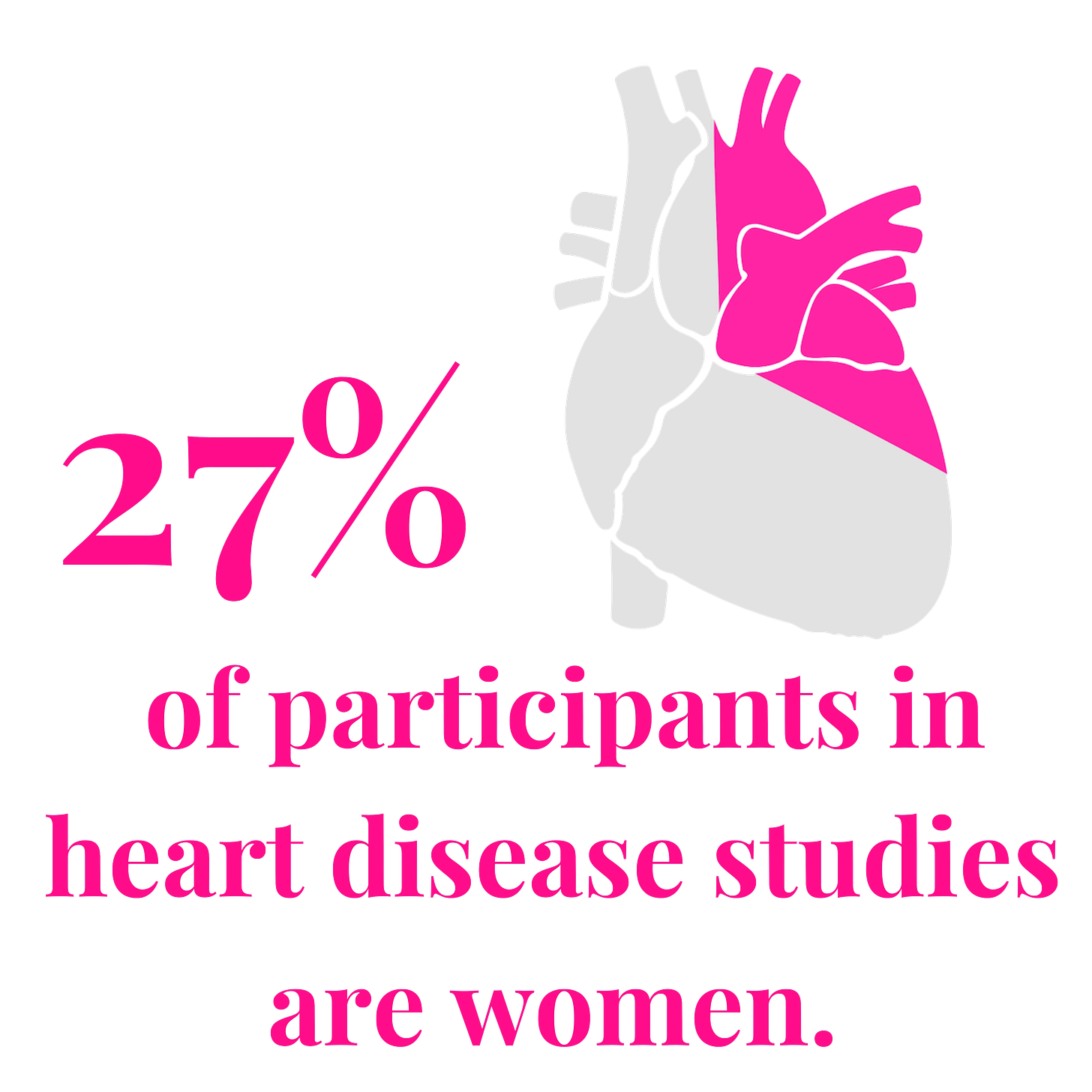

In a 2020 review of cardiovascular trials from 2010 to 2017, women made up only about 27% of participants in studies of coronary artery disease. (Jin et al. 2020)

According to the British Heart Foundation, 8,200 women in the UK died needlessly following a heart attack over a ten-year period.

Women are more than twice as likely to die of a heart attack as men. (ESC 2023)

Although women generally have a lower prevalence of cardiovascular disease (CVD) than men, a number of studies have shown that after an acute cardiovascular (CV) event, women have a greater death rate and a worse prognosis. (Suman et al. 2023)

Where do we go from here?

There's a need to add knowledge on sex and gender differences in current cardiovascular literature. The consciousness of sex and gender differences additionally needs to be integrated into cardiovascular studies. There's a need for advancement of clinical exploration in sex and gender studies that focuses on issues that are both evidence-based and meaningful to day-to-day practice, and have the eventuality to be included in future guidelines. (Suman et al. 2023) While we know women develop heart disease differently due to underlying sex factors, why do we not include them in our clinical studies? The result is women are more often misdiagnosed, less likely to respond to treatment, and less likely to be given the appropriate treatment. This needs to change.

References:

American Heart Association (2020) “Changing the way we view women’s heart attack symptoms” https://www.heart.org/en/news/2020/03/06/changing-the-way-we-view-womens-heart-attack-symptoms

Antipolis (2021) “Heart attack diagnosis missed in women more often than in men” https://www.escardio.org/The-ESC/Press-Office/Press-releases/Heart-attack-diagnosis-missed-in-women-more-often-than-in-men

Ayanian and Epstein (1991) “Differences in the Use of Procedures between Women and Men Hospitalised for Coronary Heart Disease” https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJM199107253250401

British Heart Foundation “Heart attack gender gap is costing women’s lives”. https://www.bhf.org.uk/what-we-do/news-from-the-bhf/news-archive/2019/september/heart-attack-gender-gap-is-costing-womens-lives

De Silva et al. (2022). “Sex-Based Differences in Selected Cardiac Implantable Electronic Device Use: A 10-Year Statewide Patient Cohort” https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/JAHA.121.025428

El Khoudary et al. (2020) “Heart disease risk in women increases leading up to menopause; early intervention is key” https://newsroom.heart.org/news/heart-disease-risk-in-women-increases-leading-up-to-menopause-early-intervention-is-key

European Society of Cardiology, (2023) “Women more likely to die after a heart attack than men” https://www.escardio.org/The-ESC/Press-Office/Press-releases/Women-more-likely-to-die-after-heart-attack-than-men#:~:text=Prague%2C Czechia – 22 May 2023,Society of Cardiology (ESC).

Gurwitz, Col and Avorn. (1992) “Exclusion of the elderly and women from clinical trails in acute myocardial infarction”. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1512909/

Jin et al. (2020) “Women’s Participation in Cardiovascular Clinical Trails From 2010 to 2017” https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32065763/

Nadarajah et al. (2024) “Inequalities in care delivery and outcomes for myocardial infarction, heart failure, atrial fibrillation and aortic stenosis in the United Kingdom” https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanepe/article/PIIS2666-7762(23)00138-2/fulltext

O’Donoghue, M et al. “Heart disease: 7 differences between men and Women. Brigham and Women’s Hospital.”https://give.brighamandwomens.org/7-differences-between-men-and-women/

Regitz-Zagrosek et al. (2016) “Gender in cardiovascular diseases: impact on clinical manifestations, management, and outcomes” https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28329228/

Suman et al. (2023) “Gender and CVD - Does It Really Matters?” https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36690310/

Tamargo et al. (2017). “Gender differences in the effects of cardiovascular drugs” https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28329228/

“The Heart Disease Gender Gap” Harvard Health. https://www.health.harvard.edu/heart-health/the-heart-disease-gender-gap

Wilkinson et al. (2019) “Sex differences in quality indicator attainment for myocardial infarction: A nationwide cohort study” https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30470725/

Wise et al. (2016) “Women with endometriosis show higher risk of heart disease” https://www.bmj.com/content/353/bmj.i1851

World Health Organization (WHO) “Global Health Data” https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/342703/9789240027053-eng.pdf?sequence=1